As 2025 comes to an end, I thought it was time for me to share some of my favorite scientific stories of 2025. My focus sits at the interface of tissue engineering, microfluidics, and organoid models. In short, I am trying to build organoids-on-chip that integrate vascular and immune compartments. Because I work daily on specific organ systems and tend to be more driven by technological advances than by fundamental biology, this list is inevitably biased. These are simply papers published in 2025 that I found myself coming back to, papers I’ve read multiple times this year.

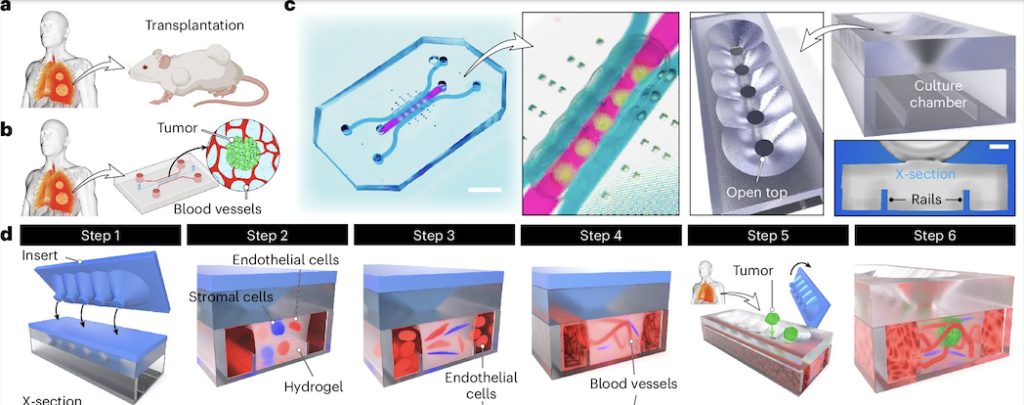

1/ A tumor-on-a-chip for in vitro study of CAR-T cell immunotherapy in solid tumors

This is probably my favorite paper of the year, from the lab of Dan Huh published in Nature Biotechnology, tackling a major bottleneck in immuno-oncology: CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors. While CAR-T cells work extremely well in blood cancers, solid tumors remain a tough challenge, largely because of the complex tumor microenvironment and physical barriers. In this study, the authors built a vascularized tumor-on-a-chip that can be perfused and directly targeted by CAR-T cells, allowing CAR-T trafficking, infiltration, and function to be studied under much more realistic conditions. What blows my mind here is how far the system is pushed. This is not just a proof-of-concept model. The platform is used to generate clinically relevant readouts and uncover new insights into CAR-T behavior in solid tumors. The amount of work within this paper is insane, congrats to the team!

Note: Another model dealing with the same challenge was proposed by the Peter Loskill group in 2024, read DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2024.04.018 if curious.

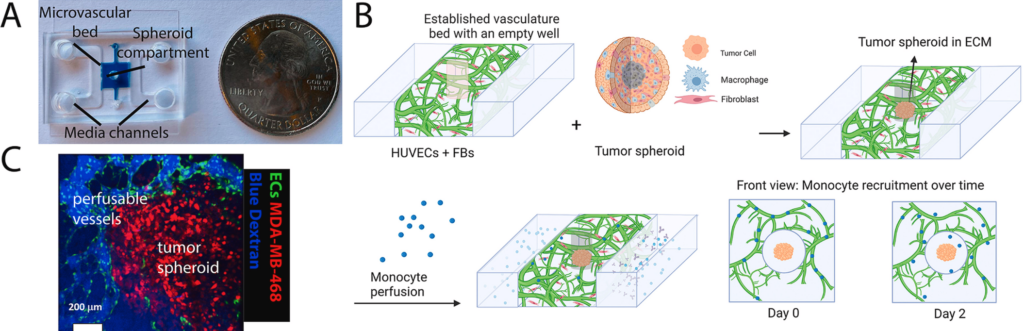

2/ Patient-specific vascularized tumor model: Blocking monocyte recruitment with multispecific antibodies targeting CCR2 and CSF-1R

Another study using the same classic microfluidic device from Roger Kamm’s lab in Biomaterials, also very cool. It’s pretty amazing to see how, in just a few years, we’ve been able to recreate immune cell recruitment to tumors in vitro, much like what happens in patients.

Using a vascularized microfluidic platform, the authors integrated patient-derived tumor fragments next to a perfused human microvasculature and circulated immune cells through the system. Monocytes are actively recruited from the vessels into the tumor via chemotaxis, closely mimicking in vivo behavior.

They identified CCL2 and CCL7 as key drivers of this process and show that recruitment can be blocked using a multispecific antibody targeting CCR2 and CSF-1R. Importantly, responses differ across patients, highlighting the platform’s potential for personalized immunotherapy testing.

Note: With the FDA’s new push to phase out animal models in drug development, there’s a real opportunity to speed up the adoption of human-relevant microphysiological systems. The two papers above are great examples of how vascularized tumor-on-chip models can go beyond descriptive.

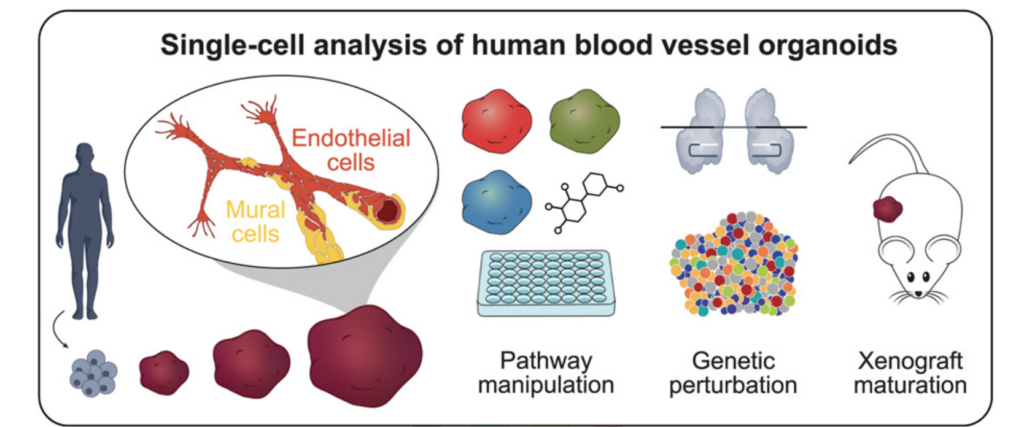

3/ Fate and state transitions during human blood vessel organoid development

A beautiful cell atlas of developing vascular organoids from Barbara Treutlein’s lab in Cell. I won’t go into too much detail here (I’m definitely biased), but if you’re working with BVOs, this paper is an amazing resource. It’s very rich in information, carefully executed, and clearly lays out what’s next for the field: better interaction with other tissues to build organ-specific vasculature, and the incorporation of vascular flow.

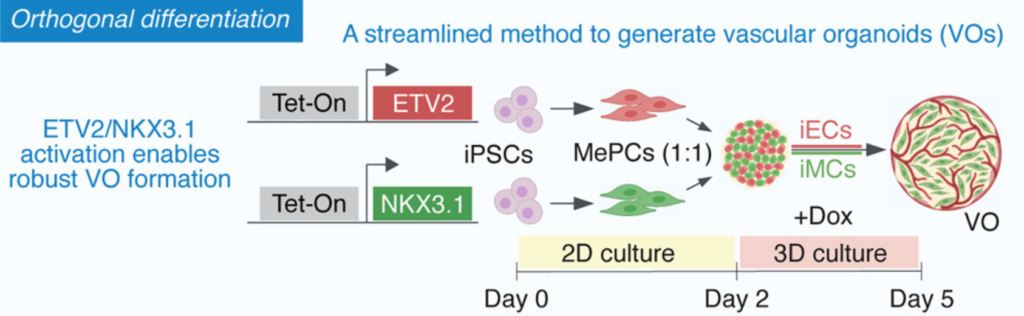

4/ Rapid generation of functional vascular organoids via simultaneous transcription factor activation of endothelial and mural lineages

This paper from the group of Juan Melero-Martin published in Cell Stem Cell presents another way to generate BVOs via orthogonal activation of the transcription factors ETV2 and NKX3.1.

Instead of relying on generic organoid self-differentiation, the authors use simultaneous transcription factor activation to drive both endothelial and mural lineages in hPSCs. What I really like here is the mindset shift: vascular identity is actively engineered and controllable, making the system easier to adapt to different contexts. I also really like the final figure, showing blood flow recovery in ischemic mouse limbs, as well as enhanced functional engraftment of pancreatic islets in mice. Very neat and quite spectacular results. If you’re interested, I highly recommend listening to the genesis of this story, as detailed by Juan Melero-Martin himself on The StemCell Podcast, Episode 307: https://stemcellpodcast.com/ep-307-vascular-biology-featuring-dr-juan-melero-martin

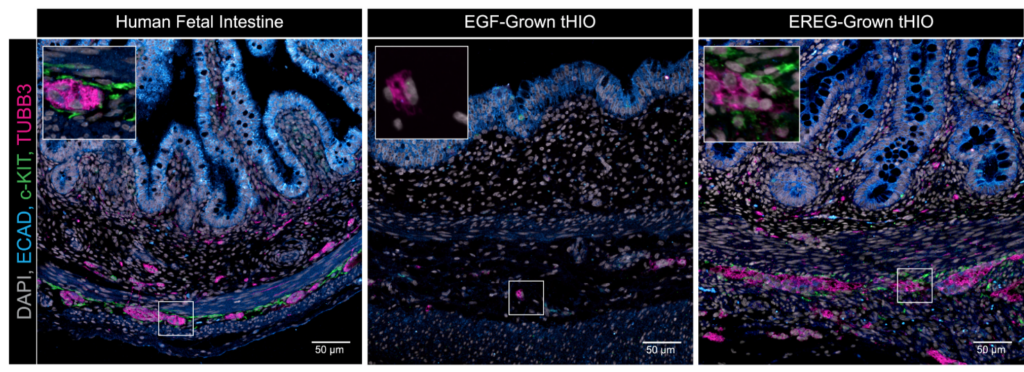

5/ Coordinated differentiation of human intestinal organoids with functional enteric neurons and vasculature

Bringing together one of the key leaders in vascular biology, Rafii Shahin, with one of the key leaders in epithelial organoids, Jason spence, in this Cell Stem Cell paper.

They introduced a new method to make more complex human intestinal organoids that feature functional neurons, endothelial cells, and organized smooth muscle, by incorporating EPIREGULIN (EREG) in their organoid differentiation protocol.

I like the effort to show perfusable vasculature in vitro, even though it feels more like an early but promising step. I’d love to see how these organoids behave once integrated into my own microfluidic chips!

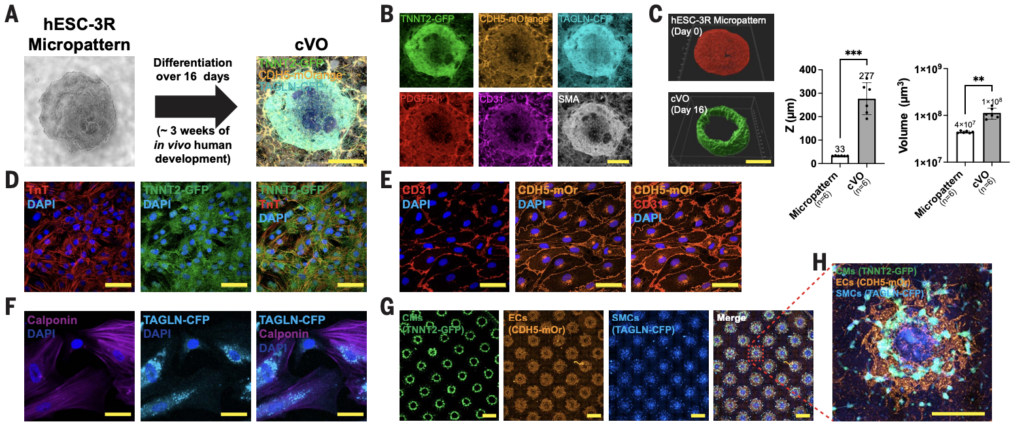

6/ Gastruloids enable modeling of the earliest stages of human cardiac and hepatic vascularization

A really beautiful and technically strong paper from Oscar Abilez and the lab of Joseph Wu at Stanford, published in Science, tackling vascularization at the early stages of cardiac and hepatic development.

Using four hPSC fluorescent reporter systems and spatially micropatterned hPSCs with a well-tuned growth factor and small-molecule cocktail, they generated cardiac organoids with spatially organized, branched, and lumenized vasculature.

The use of fluorescent reporter lines makes the system extremely informative, allowing non-destructive tracking of multiple lineages as the organoids self-organize. A very elegant example of how engineering and developmental biology can come together to push vascularized organoid models forward. I know they’re currently working on incorporating vascular flow into these models using some very innovative microfluidic designs, so I can’t wait to see what comes next!

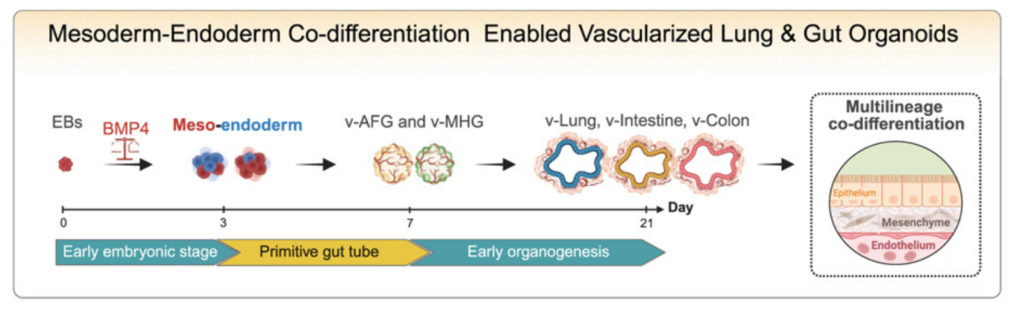

7/ Co-development of mesoderm and endoderm enables organotypic vascularization in lung and gut organoids

This paper from Mingxia Gu’s lab published in Cell makes a strong conceptual point: organ-specific vasculature built alongside the organ.

By using a mesoderm-endoderm co-differentiation strategy, the authors generated vascularized lung and intestinal organoids with endothelial and mesenchymal cells that actually acquire organ-specific features. This directly addresses two long-standing issues in the field: poor vascularization of gut organoids, and vasculature that remains generic and non-organotypic.

What I really like is the shift away from the assembloid approach, which are created by combining two mature organoids and are inherently limited in replicating physiological tissue vascularization. A simple but powerful idea that may well be key for future vascularized organoid models, especially as we start thinking about adding even more complexity, like immune compartments.

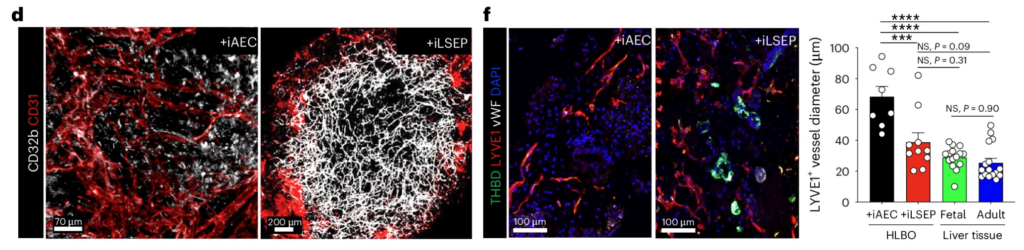

8/ Self-organization of sinusoidal vessels in pluripotent stem cell-derived human liver bud organoids

In a similar vein, this paper from Takanori Takebe’s lab in Nature Biomedical Engineering hows the generation of true sinusoidal vasculature, not generic endothelial networks. Using PSC-derived liver bud organoids, the authors showed that sinusoidal-like vessels can self-organize when the right developmental cues are in place. WNT2-mediated crosstalk between endothelial and hepatic cells drives both hepatocyte maturation and the formation of a branched, liver-specific vascular network.

Intravital imaging shows fully perfused human vessels with sinusoid-like features, with absolutely stunning images (this group really sets the bar here, see also DOI: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.102433 for their mind-blowing live imaging of perfusable vasculature in vivo).

One result I particularly liked is the functional coagulation readout. After transplantation into a haemophilia A mouse model, the liver bud organoids form human sinusoidal endothelium that secretes active FVIII, leading to a clear rescue of the bleeding phenotype.

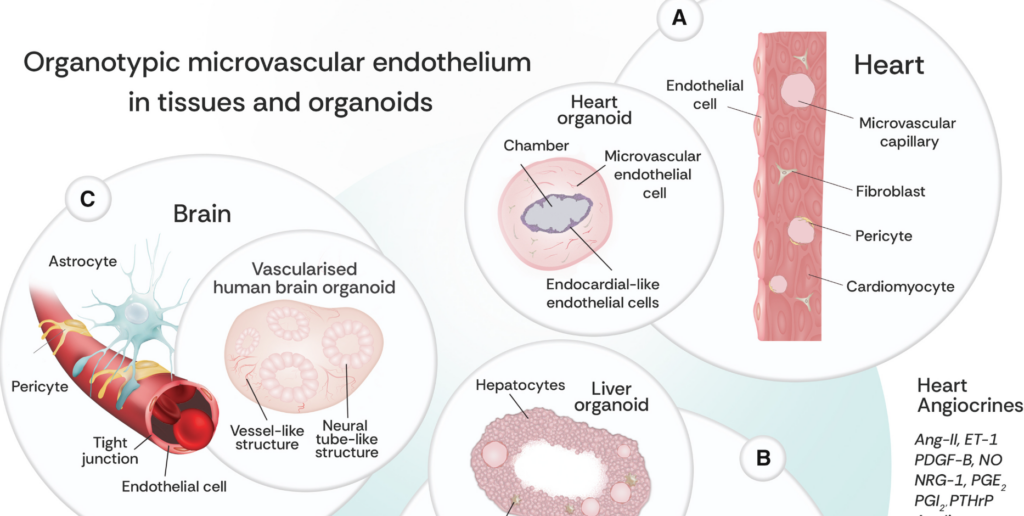

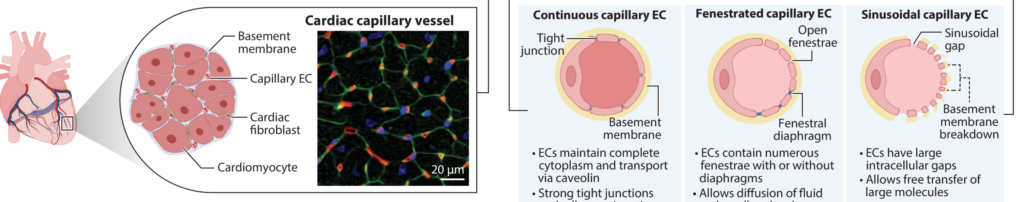

9/ Endothelial specialization and angiocrine factors are critical for vascularized organoid models (Review)

Super nice review from Rebecca Fitzsimmons and James Hudson in Cell Reports Medicine addressing a topic discussed in many of the papers I mentioned above: the organ specificity of the vasculature. A great resource for everyone working in the field, as efforts to generate organ-specific blood vessels in organoids are becoming more and more prominent.

The key message is that we need to start engineering organ-specific vascular identities in our vascularized organoid models. This review is a very helpful resource for anyone working on vascularized organoids, especially as the field increasingly shifts toward building more complex physiologically relevant models.

10/ Microvascularization in 3D Human Engineered Tissue and Organoids

A classic Annual Reviews paper tackled by Yu Jung Shin, Dina Safina, Ying Zheng, and Shulamit Levenberg, summarizing recent breakthroughs in microvascular engineering. Everything you need to know to stay up to date if you’re working in the field. Thanks to the authors for putting this together in such a clear and well-organized format!

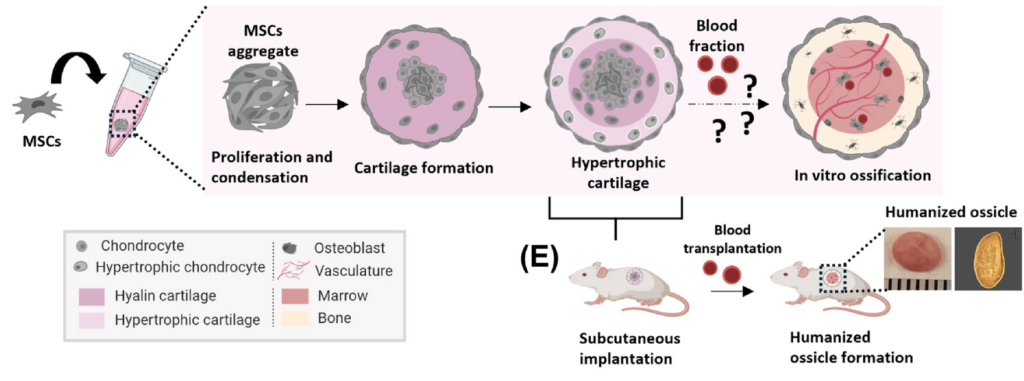

11/ Human bone marrow organoids: emerging progress but persisting challenges

Ok, time to add an immune twist to the list, with what is one of the main focuses of my postdoc: Bone Marrow Organoids (BMOs). Recently, BMO protocols have been developed (see DOI: 10.1038/s41592-024-02172-2 and DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-0199), adapted from BVO protocols but using a much richer cocktail of growth factors to give rise to a wide range of hematopoietic cells, including red blood cells and immune cells.

Using such elaborate protocols, with proper embedding in ECM, these models can recapitulate the complex architecture of the human bone marrow, including the different niches that may be crucial for the development of PSC-derived bona fide hematopoietic stem cells. These models are likely to become extremely popular in the field, given the tremendous opportunities they offer for exploration.

Paul Bourgine wrote a nice and concise review in Trends in Biotechnology, summarizing these recent advances and the remaining challenges.

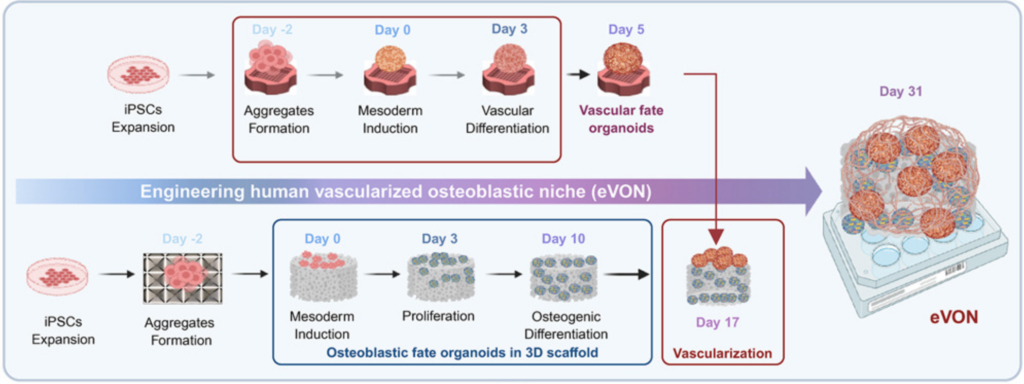

12/ Macro-scale, scaffold-assisted model of the human bone marrow endosteal niche using hiPSC-vascularized osteoblastic organoids

And precisely, one of these challenges is tackled in this Cell Stem Cell paper from the groups of Ivan Martin and Andrés García-García. The recent BMO protocols discussed above, despite their innovative character, lack a bone compartment and are therefore not suitable for properly modeling the human BM endosteal niche. Moreover, they remain at the micrometer scale, resulting in vascular structures that are non-physiological in shape and size. To address this, the authors optimized the generation of osteoblastic/vascular fate organoids and cultured them on porous 3D hydroxyapatite scaffolds instead of conventional Matrigel-based matrices. These scaffolds resemble the architecture of trabecular bone and mimic the inorganic composition of the native BM endosteal microenvironment.

I like how this study highlights that faithfully recapitulating complex niches may sometimes require moving beyond minimal organoid systems and embracing smart engineering approaches. Definitely a valuable addition to the growing toolkit for modeling human hematopoiesis and bone marrow biology in vitro.

13/ Organoids as models of immune-organ interaction

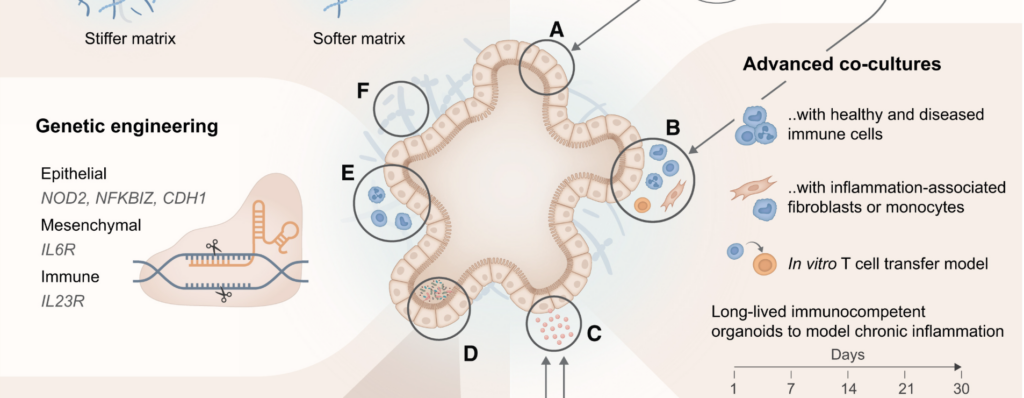

An amazing review, by Marius Francisco Haerter, Timothy Recaldin and Nikolche Gjorevski from the Institute of Human Biology and Pharma Research and Early Development (pRED) at Roche, published in Cell Reports, on the incorporation of immune cells within organoid models. Great work on the illustration as well which makes the paper very smooth to read. Super well written, straight to the point while not sacrificing scientific detail.

My favorite part is of course the discussion of organ(oid)-on-chip models and the logic behind their development. I always present the potential of organoids-on-chip as the best of both worlds, taking advantage of organs-on-chips and organoids while avoiding the drawbacks of both systems. The authors nailed it with this sentence: “Although first-generation organ(oid)-on-chip approaches have made strides in enhancing accessibility and interfacing with adjacent tissue compartments, they often do so by ceding some of the core physiological advantages of organoids. Indeed, culturing organoid-derived cells in monolayer format within organs-on-chip devices grants luminal access and proximity to a vasculature-like channel, but precludes intrinsic morphogenic processes like autonomous lumen formation, patterning, and budding. It is these features that render organoids superior to conventional flat cell culture.”

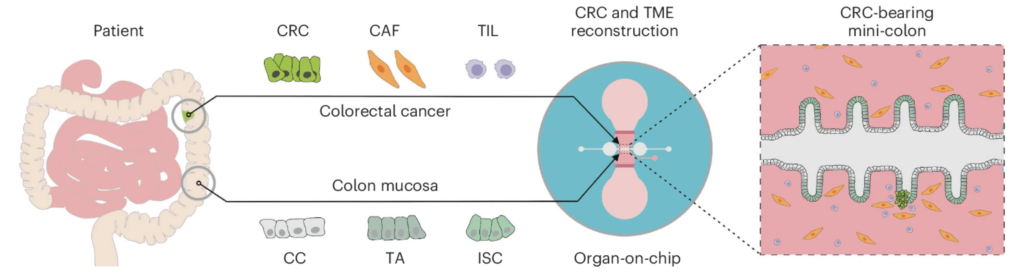

14/ Patient-derived mini-colons enable long-term modeling of tumor–microenvironment complexity

A super nice story from Matthias Lutolf’s lab in Nature Biotechnology, bringing together patient-derived tissue models, microfluidics, cancer, and immune cells. Using their now classic gut-on-chip device (initially introduced in 2020 by Mikhail Nikolaev et al., see DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2724-8), they incorporated several key elements of the tumor microenvironment to model and study colorectal cancer.

As discussed in the review mentioned above, using this kind of organ-on-chip design is a game changer, as it allows direct access to the gut lumen, a guided arrangement of tissue and tumor that is much more “in vivo-like”, and the incorporation of cancer-associated fibroblasts and/or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, which are central to this study. This is a wonderful example of how new technology enables us to tackle scientific questions that could not be addressed using conventional culture systems.

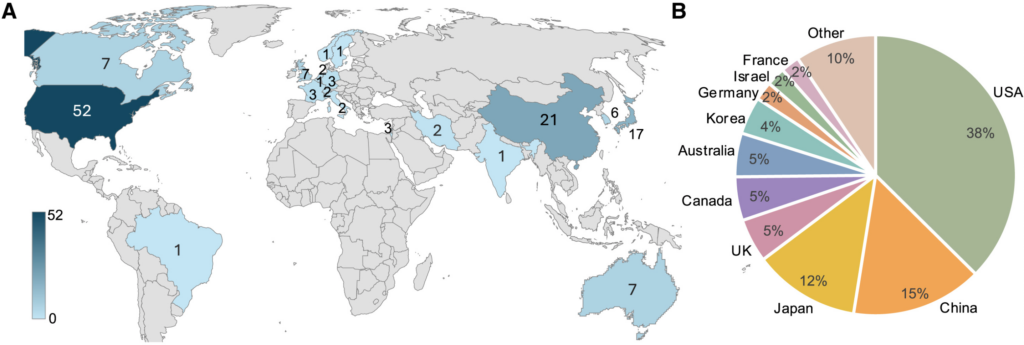

15/ Pluripotent stem-cell-derived therapies in clinical trial: A 2025 update (Review)

To finish, a Cell Stem Cell review from Agnete Kirkebey, Heather Main, and Melissa Carpenter, published in the first days of 2025, provides an overview of stem-cell-derived therapies currently in clinical trials. They report a total of 83 hPSC-derived products undergoing testing in 115 clinical trials worldwide, which is pretty amazing for the field! As my supervisor wrote to us for the winter holiday: “Together we make some little dents in the fabric of knowledge and with our discoveries and work, whatever that is, attempt to improve the lives of a few and maybe of many”. I’m not sure how these clinical trials progressed over the year or what conclusions can be drawn so far, but please let me know if you do.

Leave a Reply